Chinese Glass snuff bottles from the Qing dynasty

The first examples of glass artefacts in China date back to the 6th century B.C . In the beginning, and for centuries, glass and its rudimentary manufacturing technique were used to merely imitate other materials, in particular jade, as shown by archaeological findings. The improvements glass then underwent were sporadic without any major artistic developments even under the brilliant Han, Tang or Song dynasties, from which few objects of major importance have reached us.

In the 14th century, at the end of the Yuan dynasty (1260-1368), a production centre was set up at Boshan in the Shandong region. It continued to exist under the Ming dynasty and even provided labour to workshops of Emperor Hongwu (1368-1398) detailed archives indicate that in 1370 a glass maker was called upon for the manufacture of glass-bead curtains and lamps. Canton was to become the second largest production centre. This long period of lack of interest in China for glassware was undoubtedly due to its preference for ceramics. Having gained perfect mastery over this ancestral art, the Chinese preferred ceramics to glass.

Kaolin and porcelain, unknown to the Europeans for a long time, gave the Chinese secrets of fine work, tranlucency, purety and boundless possibilities in terms of designs and patterns in the field. Glassworks were thus shut down in the middle of the 17th century in the troubled “Transition” period, to be reopened only under the new Mandchu dynasty of the Qings, a period of previously unequalled Imperial patronage.

It was in this period that the Chinese discovered tobacco in the form of powder to be taken as “snuff” and attributed medicinal virtues to it, which were soon forgotten in favor of the highly fashionable nature of its use. The problem of packaging was soon to arise, however, since China’s humid climate did not favour proper preservation of tobacco in bottles with wide openings like those used in Europe. It was then that ordinary medicine bottles began to be used for carrying tobacco, with decorative stoppers fitted with hermetic corks to close the openings, and tiny shovels to extract the tobacco from the bottle. The taking of snuff became a status symbol. Along with the Emperor, the Court, high officials, officers and the Mandarin class all indulged in it, contributing to the development of the snuff bottle. The snuff bottle was a functional object but also had to reflect the status of the owner and user. In other words, it was an “objet d’art” and a new medium for the application of all the main decorative techniques of the period.

At the end of the 17th century, with the new enthusiasm shown by Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722) for glass objects and the rapid development of the taking of snuff within the Forbidden City itself, the first glass snuff bottles were born: truly an Imperial creation.

Europeans played an important role in this enterprise. A contemporary of Louis XIV with whom he shared many similarities, Kangxi governed his country with great authority and was a patron of the arts and letters. He welcomed many jesuits to his court, who were then unscrupulously put to use for their different skills by the artisic, literary and scientific departments of the Imperial palace. Many gifts, including glass objets, reached the Emperor from Europe and he discovered the material and its hitherto unsuspected uses with interest. He found Boshan or Canton made nothing comparable, so ordered the creation of the glassworks in 1696 within the walls of the Imperial Palace under the guidance of a german Jesuit called Kilian Stumpf (1655-1720) and called for the best artisans of the Empire to work in it.

European technical contribution was considerable. The formula for manufacturing glass improved and allowed for greater purity and malleability, even though snuff bottles did show lines of fine cracks on the inner and outer surfaces. This flaw, known in Europe, came from an excess of alkalinity in the basic composition of the glass. A characteristic feature of old glass snuff bottles and a proof of foreign intervention, today this helps us date objects. With time, the technique of blown-glass progressed and engraving and diamond-based cutting began to appear. Under Kangxi, the main colours used for snuff botttles were red, blue and yellow (Imperial colours) always in monochrome but with gold, silver or multi-coloured staining effects, drawing their inspiration from Venetian glass work, which constituted the first designs. The early shapes remained simple and often rounded, but were also reminiscent of Bohemian glass with work in facets around circular panels, while more European models, much appreciated by the Emperor, such as the fob watch, called for new designs.

Two other important European contributions date back to this period : the technique of enamelling, and the introduction of “Cassius purple” allowing for a new range of colours around a pink base. Together they were to generate superb works of art on metal, glass and porcelain.

Kangxi, very taken with enamel-work on glass, called for the few Chinese specialists that existed in the country. Cantonese artisans, probably trained by Europeans, thus went to the Imperial Palace to work from 1716. They preceded the French Jesuit Jean Gravereau, an expert enameller, who accepted in 1719 to work for the Emperor and gave a new dimension to this decorative art. Unfortunately, no enamelled glass snuff bottle marked from the reign of the Emperor Kangxi is recorded today. There are two, however, that are attributed to this period. One through technical or decorative analogy with a small “marked” bowl belonging to this period, and the other through its similarity with an enamelled metal snuff bottle bearing the Kangxi mark. These two glass snuff bottles also reveal the technical limitations of the period with regard to the complex process of glass-enamelling. The annealing temperature had to be very precise so that the colour of the enamel snuff bottles or the shape of the object were not altered by excessively high temperatures.

Under the reign of Yongzheng (1723-1735), patronage continued but the Emperor often left the Forbidden City in Beijing for the magnificent residence of the Imperial gardens in Yuanming Yuan. As a result of his keenness for the art of glass-making, he decided to transfer a part of the glass-works there. As with the previous reign, snuff bottles from this period are extremely rare today. Pure forms in monochrome were much in favour and constituted most of the production, but with a wider range of shades. Glass snuff bottles imitating realgar ( a stone containing arsenic used in Taoist alchemy) date back to this period. Yongzheng liked snuff bottles and offered them for annual traditional festivals. Indeed, in the 18th century, the snuff bottle was to accompany all major events.

The rarity of enamelled glass snuff bottles from this period is probably due to the fact that the technique for making them was not yet very reliable. One single enamelled glass snuff bottle bearing the mark of the Emperor Yongzheng is known today, in the National Museum of taipeï in Taiwan. It is in the shape of a piece of bamboo enamelled in green, is decorated with leaves and small insects, and carries the Imperial stamp on its base in the centre of a contour showing a symbolic mushroom. The Palace archives mention the date of manufacture as being 1728.

These two reigns saw rapid developments in glass manufacture, leading to new methods in glass decoration, such as sculpture, overlay and engraving. These were the first signs of what was to be the splendour of glassmaking in the following reign.

Under the reign of Qianlong (1736-1795) collaboration with missionaries was enhanced and patronage extended. Glass-making returned, to a large extend, to the Palace of Beijing. After a brief transition period, the Emperor surrounded himself with Jesuits capable of supervising some of the Imperial production sites of these “objets d’art”, thus perfecting the basic techniques acquired and taking them to the highest levels.

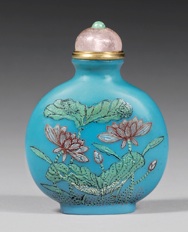

Enamelling on glass reached its peak in this period. Mastery of the technique of pink enamel led to the making of masterpieces, most of them preserved in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Some of these have purely Western designs with human figures, landscapes and architectures, while others have Chinese patterns with landscapes, plants and birds, taken from traditional painting or porcelain decoration.

In 1740, the arrival in the glassworks of the Jesuit Gabriel-Léonard de Broussard ushered in a prolific and high quality period during which glass snuff bottles were produced for the Imperial collections or for presentation on specific occasions such as birthdays or the new year. These snuff bottles were often monochrome, translucent or opaque, in more characteristically Chinese shapes with masks and rings on the shoulders, or resembled bottles more traditionally carved in jade or agate. While the faceted style remained, the central panels and cut sides often had sculpted backgrounds or were incised with calligraphy. Emperor Qianlong, who was a poet, has his poems engraved on glass snuff bottles, some examples of which exist even today. Glass-making still carried with it a strong desire to imitate other materials however, and a highly sophisticated technique made this increasingly possible even through cracking in the glass remained a problem in the early part of the reign. Rock crystal was imitated to perfection , as were amethyst, jade, aquamarine, agate, realgar and amber. The mark Qianlong stamped under the base indicated either Imperial manufacture or commissioning.

The shape and designs of bottles were obtained by blowing in the air, by using a mould, or by sculpting the glass directly. The Qianlong reign was a celebration of the art of sculpted glass. Similarity in work and style between these snuff bottles and models of bottles in nephrite or agate confirms the idea that they were made by craftmen from the Imperial Palace.

These heirs of a centuries-old tradition were the ones who worked on glass in the 18th century. Techniques developed in previous reigns led to this technique, likened to overlay sculpture. Close to cameo work, it involves carving a design on several layers of glass that are superimposed or juxtaposed, so as to take full advantage of the different colors or stains of each layer. The skill of the cutter lay in identifying the best possible combinaison of colours so that they were in harmony with the subject of the design, and then to carve the whole with finesse and vigour following the shape of the bottle for a final effect of perfect balance. The first shades used were red over a transparent or “flaked” background, followed by blue and green, and finally a very wide palette of colours.

At the height of the technique , up to three colors were superimposed on a primery background and up to eight shades were juxtaposed.

Snuff bottles of this type are rare and always of a very high quality. Designs represent varies themes from classical Chinese iconography, literature, Buddhism and Taoism, as well as foreign influences, such as Mughal style. From 1758 to 1760, a gradual drop in Jesuit involvement led to the taking-over of the Imperial glass-works by the Chinese. However, this heritage was not maintained for long.

Along with this Imperial production and the democratization of snuff bottles, private workshops also manufactured high-quality glass snuff bottles. Originally from Canton or Boshan, the artisans employed in the Imperial glassworks worked for approximately eight months in the year and then went home, since a fear of fires and concerns for safety caused the kilns to be closed in the hot summer months. These artisans were therefore able to carry and transmit their skill and expertise to their home regions, certainly contributing to the growth of glassworks which were much freer in approach since they were away from centralized power.

High-quality glass-enamelling persisted in the second half of the 18th century under the patronage of Qianlong, and then under Jiaqing (1796-1820) with a singular group of bottles carrying the mark Guyuexuan (Old moon Pavilion). This pavilion , located in the precincts of Yuanming Yuan, was to welcome Qianlong during his retirement and the snuff bottles were intented for him. They show a high level of finesse in their execution. A new decorative method was here accompanied by embossed sculpted motifs which were then enamelled, often in very bright colors. Rare examples of bottles carrying the Guyuexuan mark are attributed to the Yangzhou Glassworks , which in the second part of the 18th century were brought in to supplement Imperial production. The lightness of the enamel and the fluidity of the designs is what characterizes the beautiful products of this workshop, renowned in the following century for completely different snuff bottles.

At the dawn of the ninetheenth century, patronage declined along with the quality of manufacture. Subsequent sovereigns did not have the rigour required to maintain the artistic level reached in an ageing China where a gradual weakening of Imperial power seemed inevitable. Anf yet, each reign produced interesting snuff bottles , surprising for the quality of their craftmanship, their subject-matter or the fact of their having been owned or ordered by important historical figures who put their mark or name on them.

Glass snuff bottles said to be of the “Yangzhou School” stand apart easily from all creations of the 19th century. Created in one single workshop, they follow a specific basic model : a generally opaque layer of glass covered with a second simple monochrome layer or else with numerous juxtaposed stains of color. Carved in a very slightly embossed style, the design often draws on a pictorial style originating in Yangzhou, a typical reflection of a Mandarin aesthetic, and carries seals and inscriptions. Very easily recognizable, these snuff bottles sometimes show an astonishing pairing of colors. This school was innovative in glass snuff bottle-making. For instance, some bottles were signed by their creator, an individual act rarely observed in other workshops and unthinkable in the Imperial context, characterized as it was by the total anonymity of its artists.

Just two centuries were required to bring about the birth, the peak and the death of what constituted the art of glassmaking and the history of snuff bottles in China. The decline of these arts coincides with the fall of the Qing dynasty. Cigarettes then replaced snuff in the early 20th century and the Imperial glassworks were closed in 1911 with the fall of the dynasty and the last Emperor Xuantong. The study of Chinese glass and snuff bottles has come out of obscurity only over the last fifty years. And yet, despite a great deal of research and studies undertaken in China, North America and the West generally, it remains difficult to exactly date and attribute many snuff bottles. The recent opening of he Imperial archives in the Forbidden City is enabling new developments but Chinese snuff bottles remain one of those artistic fields where research tends to outweigh positive affirmation.